How to Choose the Right Switch for Your Electronics Project

You’re staring at the Bill of Materials (BOM) for your latest PCB design. The microcontroller is chosen, the power management is sorted, and the enclosure is modeled. Now, you just need a switch. It sounds simple until you open a distributor catalog and are hit with 50,000 options: tactile, toggle, rocker, slide, DIP, illuminated, sealed, unsealed.

Here is the reality we see often in the manufacturing world: The switch is frequently the last component selected, but the first one to fail.

Choosing the wrong switch isn't just about whether it fits on the board. A mismatch in electrical specs can lead to welded contacts. A poor choice in haptics can make a premium device feel like a cheap toy. At HX Switch, we’ve helped OEMs navigate these decisions for years. We know that the difference between a successful product and a field recall often comes down to the smallest electromechanical component.

This guide moves beyond basic definitions. We’re going to walk through the engineering framework you need to match the specs to your specific application constraints.

Define Your Electrical Load Requirements

Before you worry about how the switch looks or feels, you have to ensure it won't burn out. This is where most junior engineers make mistakes—they look at the voltage but ignore the load type.

Voltage and Current Ratings

A switch rated for 125VAC is not necessarily safe for 12VDC at high currents. DC arcs are harder to extinguish than AC arcs because the current never crosses zero. Using an AC-rated switch for a high-current DC application can lead to sustained arcing, heat buildup, and eventual failure.

The Golden Rule: Always select a switch with a rating at least 25% higher than your circuit’s maximum load. If your circuit draws 4A, look for a switch rated for 5A or 6A.

The "Hidden" Killer: Inrush Current

Here is what most datasheets don't scream at you: Resistive loads (like a heater) are easy on contacts. Inductive loads (like motors) and Capacitive loads (like power supplies) are brutal.

When you turn on a motor, the initial "inrush" current can be 10x to 20x the steady operating current. That tiny millisecond spike is enough to pit or weld the contacts of an underspecified switch together. If you are driving a motor or a large LED array, you either need a switch with a high "horsepower" rating or you need to use the switch to trigger a relay or MOSFET that handles the heavy lifting.

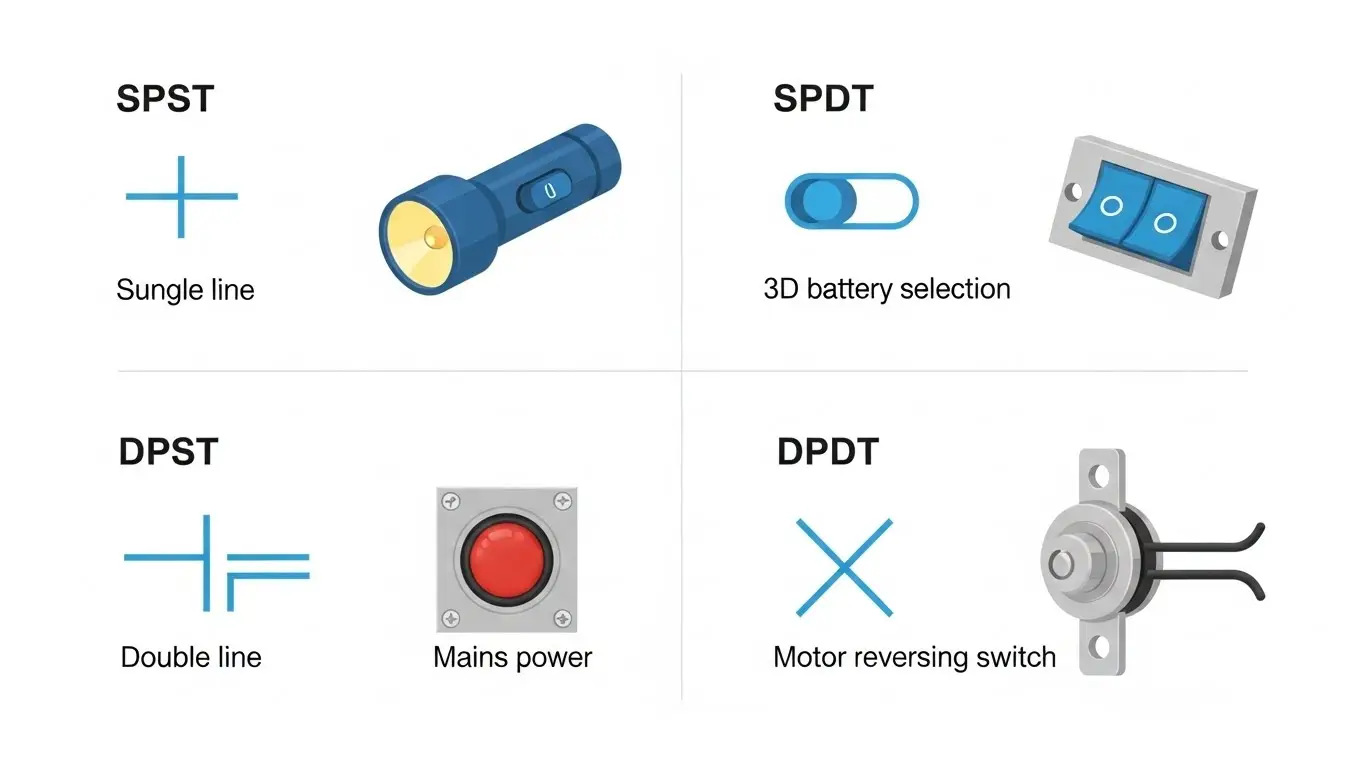

Decode the Circuit Logic (Poles and Throws)

Once you know the power, you need to define the logic. This is arguably the most confusing part of switch nomenclature for beginners, but it follows a simple pattern.

- Poles: How many separate circuits are controlled?

- Throws: How many positions can the switch activate?

Quick Selection Cheat Sheet

| Acronym | Name | Best Used For... |

| SPST | Single Pole, Single Throw | Simple On/Off. Turning on a flashlight or resetting a microcontroller. |

| SPDT | Single Pole, Double Throw | Selection. Toggling between two power sources (Battery vs. USB) or two modes (High/Low). |

| DPST | Double Pole, Single Throw | Safety. Cutting both Live and Neutral lines simultaneously in mains power applications. |

| DPDT | Double Pole, Double Throw | Complex Control. Reversing the polarity of a motor (forward/backward) or switching two different signals at once. |

Choose the Mechanical Function and Form Factor

Now that the electronics are safe, how will the user interact with it? This is where mechanical design meets user experience (UX).

Momentary vs. Latching

- Momentary (Non-locking): The connection is only active while you are physically pressing the actuator. Think of a keyboard key, a doorbell, or a reset button. This is standard for digital signals where a microcontroller detects a pulse.

- Latching (Locking): The switch stays in position after you release it. Think of the power button on an old amplifier or a light switch. This is typically used for hard power control.

Selecting the Right Form Factor

- Tactile Switches: These are the workhorses of modern electronics. They are compact, usually momentary, and provide a sharp "click." If you are working with compact layouts, understanding tact and DIP switch fundamentals is crucial for optimizing your PCB design.

- Rocker & Toggle Switches: These provide visual feedback of the state (you can see if it's "On" or "Off" from a distance). They are preferred for industrial panels and main power controls.

- Push Buttons: Extremely versatile. They can be found in sleek, flush-mounted metal versions for medical devices or rugged, high-travel versions for arcade machines.

Environmental Factors and IP Ratings

Where will this device live? A switch that works perfectly in a climate-controlled server room might fail in a week if placed on a marine dashboard.

We often see clients over-specifying or under-specifying here. You don't always need a submarine-grade switch.

- IP40 (Standard): Good for indoor consumer electronics. Protects against solid objects (like wires) but offers no water protection.

- IP65 (Splash Proof): Can handle low-pressure water jets. Good for kitchen appliances or industrial controls that get wiped down.

- IP67 (Immersion): Can be submerged in 1 meter of water for 30 minutes. This is the minimum standard we recommend for outdoor wearables, rugged handhelds, or automotive applications.

Manufacturing Note: Sealed switches (IP67+) cost more and often have a stiffer actuation force because the internal mechanism is fighting against a rubber seal or membrane. Be prepared for that trade-off.

Haptics and "Switch Feel"

This is the specification that doesn't show up on a multimeter, but it defines the quality of your product. "Haptics" refers to the tactile feedback the user feels when pressing the switch.

- Actuation Force: Measured in grams-force (gf). A 160gf switch feels standard. A 300gf switch feels heavy and deliberate (good for preventing accidental presses in industrial settings). A 100gf switch feels light and fast.

- Travel: How far does the button go down? Tactile switches have very short travel (0.25mm), while push buttons might have 3mm or more.

- Sound: Does it click? Silence is preferred for audio equipment or hunting gear, while a crisp "snap" is desirable for computer mice and keypads to confirm input.

Why Manufacturing Quality Matters

It is easy to find a cheap switch that looks like the spec sheet. But inside the housing, materials matter.

Electrical Life vs. Mechanical Life

A datasheet might promise 100,000 mechanical cycles. This just means the spring won't break. However, if the contact plating is thin or the alloy is cheap, the electrical life might only be 10,000 cycles before the resistance becomes too high to pass a signal.

At HX Switch, we emphasize consistent contact resistance and plating quality. Whether you need gold plating for low-level logic signals (to prevent oxidation) or silver alloy for high-power switching, ensuring the inside of the switch is built to standard is what prevents field failures.

Conclusion

Selecting the right switch is a balance of electrical safety, mechanical constraints, and user experience. By following this framework—Load, Logic, Function, Environment, and Haptics—you can prevent the most common failure points before you even build your first prototype.

The Bottom Line: Don't let the switch be an afterthought. It is the primary interface between your customer and your technology.

Need help navigating the options? Whether you need a standard tactile switch or a custom IP67 assembly, browse the full HX Switch catalog or contact our engineering team to ensure your BOM is bulletproof.

Frequently Asked Questions

A momentary switch is only "active" while you are holding it down (like a doorbell). As soon as you let go, it turns off. A latching switch locks into place when pressed (like a light switch) and requires a second action to turn off.

Generally, yes, provided the voltage and current ratings are respected. However, you should never use an AC-only rated switch for high-voltage DC applications. DC arcs are much harder to extinguish and can melt the contacts of a switch designed only for the zero-crossing nature of AC power.

IP67 indicates the switch is dust-tight and can withstand temporary immersion in water (up to 1 meter depth for 30 minutes). This is ideal for devices that may be dropped in water or used outdoors in heavy rain, but it is not intended for permanent underwater use.

This is usually caused by inrush current. When a switch connects to a capacitive load or a motor, a massive spike of current flows initially. If the switch isn't rated for this spike, the heat generated can literally weld the metal contacts together, causing the switch to stick in the "On" position.

Identify the maximum current your load draws. If it's a motor or capacitor, factor in the inrush current. As a safety practice, choose a switch rated for at least 25% more than your maximum expected continuous current. If your device draws 4 Amps, choose a 5 Amp or 6 Amp switch.